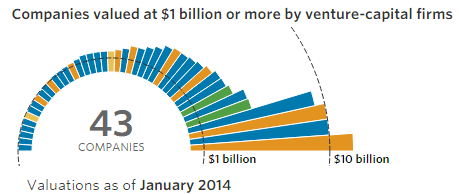

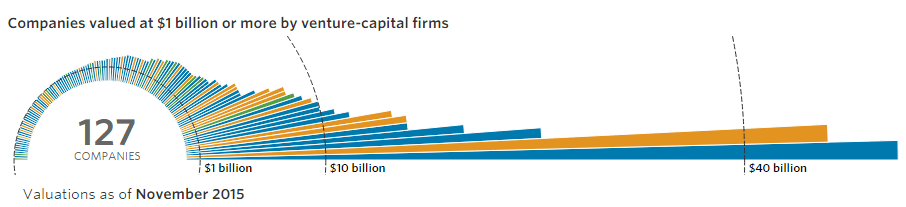

When venture capitalist Aileen Lee coined the term “unicorn” in the fall of 2013 to describe a start-up technology company that had achieved a valuation exceeding $1 billion, it was a fitting description of an exceptionally rare phenomenon. Today, in the middle of what some industry veterans are describing as a second tech bubble, unicorns almost seem ubiquitous. The infographics below – the first as of January 2014, and the second as of November 2015 – show how the number of venture-backed private companies valued at $1 billion or more has increased dramatically.[1]

The number of unicorns has nearly tripled in less than two years, which is good to the extent those valuations are supportable – “supportable” being the operative word. It is inherently difficult to value an early-stage company, especially when that company derives its value from a unique and disruptive technology. Unfortunately, the difficulty is not an abstract issue, because as spotting unicorns has become almost quotidian, determining their values correctly has become commensurately more important to the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”).

Why do federal regulators care about the value of Snapchat, a company which had almost no revenue in 2014 and whose main asset is an application used to send ephemeral “selfies”? It would be absurd, except that for the first time in history, public investors have significant direct exposure to these types of Silicon Valley start-ups. Mutual funds managed by Fidelity, T. Rowe Price, BlackRock, and many others have been purchasing shares of private companies like Uber, Airbnb, Dropbox, SpaceX, and, yes, Snapchat. In fact, according to The Wall Street Journal, the five biggest fund firms participated in funding rounds worth a combined $8.3 billion in the first three quarters of 2015, and shares of those start-ups have landed in some of the most popular mutual funds to small investors. It is the SEC’s enduring mission to protect that type of investor.

As evidenced by its increased scrutiny of mutual funds’ valuation procedures in recent months, the SEC is taking the mission seriously (as usual). Houlihan Capital has learned from both industry insiders and public sources that SEC examiners are asking more questions of mutual fund managers and board members about the methods they are using to value illiquid securities, like shares in private companies, with a special focus on start-ups.

Because mutual funds fall within the purview of the Investment Company Act of 1940 (the “Act”), the funds’ boards of directors are ultimately responsible for calculating net asset values daily “in good faith.” In the past, some boards have found adhering to the valuation requirements of the Act problematic when those requirements concern illiquid investments. For example, in 2004 the investment adviser to a mutual fund and its president were fined $800,000 by the SEC for violations relating to the improper valuation of private equity securities.

Today, one phenomenon surely piquing the interest, if not yet the ire, of the SEC is the many instances of the same security being assigned different prices by more than one mutual fund on the same date. An analysis by The Wall Street Journal of closely held technology start-ups worth at least $1 billion found 12 such occurrences. Most conspicuously, as of June 30, 2015, the T. Rowe Price Global Technology Fund valued Cloudera Inc. at $27.83 per share, while the Hartford Growth Opportunities Fund reported identical shares at $13.10.

One explanation for differing opinions of value is simply a lack of understanding of how to properly value unicorns. There are three generally accepted approaches to valuation that should be considered: the cost approach, the income approach, and the market approach.

The cost approach estimates the fair value for an asset based upon the capital necessary to create an equivalent asset. This valuation approach is most appropriate for highly capital-intensive businesses like real estate holding companies or petroleum refiners, firms whose value has an upper bound closely related to the explicit costs to construct a substitute. A start-up might be valued using the cost approach if it was struggling to remain solvent and was a candidate for liquidation. Since a unicorn is by definition a going concern, the cost approach should not be relied upon.

Nearly as unsuitable is the income approach. The income approach is based on the premise that the fair value of an asset is equal to the present value of the future earnings capacity that is available for distribution to investors in the asset. A commonly applied valuation methodology within the income approach is the discounted cash flow (“DCF”) method. Using a DCF analysis, expected future cash flows attributable to the asset are estimated and then discounted to present value at an appropriate required rate of return.

While the DCF method is fundamentally sound, it becomes suspect upon application to unicorns. How does one project discrete cash flows for a business that has no history of earnings and perhaps even no history of revenue? Furthermore, how does one determine a discount rate for such an embryonic company? Depending on the investment firm’s information rights, a company-generated budget may not even be available to assist in answering these questions. If relied upon at all, the DCF method should be used with extreme caution.

That leaves the market approach to do most of the work. The market approach references actual transactions in the equity of the enterprise being valued or transactions in similar enterprises that are traded in private and public markets. Third-party transactions in the equity of an enterprise generally represent the best estimate of fair value if they are completed at arm’s length between willing parties, which is why some mutual funds are reluctant to report a change in value of a unicorn for multiple quarters. For example, Fidelity reported the same price for Dropbox throughout 2013. This tactic is misguided, however, because, even if new company-specific information is unavailable, material changes are happening in the economy and relevant industry all the time. Moreover, a stationary value may be a red flag to the SEC indicating insufficiently proactive valuation procedures. The board of directors should incorporate all material changes (e.g., interest rates, economic indicators, regulatory reform, and the emergence of new competitors) into the valuation of illiquid securities.

The guideline public company (“GPC”) method is another valuation method within the market approach. The GPC method involves identifying and selecting public companies with financial and operating characteristics similar to the enterprise being valued. Once a publicly traded peer group is identified, valuation multiples can be derived from the ratio of enterprise values or stock prices to respective business metrics. Then, those multiples can be adjusted for growth and risk and multiplied by the same metrics of the subject enterprise to estimate the fair value of the subject enterprise’s equity or invested capital.

Typically, analysts use company earnings, EBITDA, or book value as the denominator in a valuation multiple. Unicorns usually demand more creativity because book value and income measures for the subject may be de minimus, negative or otherwise not serviceable for the approach. Houlihan Capital often uses revenue multiples or sector-specific multiples as alternatives.

Revenue multiples and sector-specific multiples offer a number of advantages in the valuation of unicorns. First and foremost, the sector-specific metrics and revenue of a unicorn are often better predictors of its future profit stream than traditional metrics. Moreover, revenue multiples remove some of the potential for bias created by eliminating firms in a sample, are less volatile than earnings multiples, and are harder to distort with accounting decisions. Sector-specific multiples go one step further: they can be estimated for firms where accounting statements are nonexistent. For instance, an investor in a unicorn social network company may only receive periodic updates on the company’s number of members. Still, a value may be imputed by looking to public data on, say, Facebook and using the ratio of enterprise value to members.

When valuing a unicorn, the truth of the matter is that there is no formulaic solution. It takes expert knowledge and experience to arrive at robust conclusions. Even if a board of directors to a mutual fund holding illiquid securities has an expert in-house valuation team, best practice is to enlist an independent third-party valuation firm like Houlihan Capital.

Houlihan Capital is a leading, solutions‐driven valuation, financial advisory and boutique investment banking firm committed to delivering superior client value and thought leadership in an ever‐changing landscape. The firm has extensive experience in providing objective, independent and defensible opinions of value that meet accounting and regulatory requirements. Our clients include some of the largest asset managers around the world, and ’40 Act funds, private equity funds, hedge fund advisors, fund administrators, and other asset management firms benefit from Houlihan Capital’s comprehensive valuation and financial advisory services. Houlihan Capital is SOC-compliant, a Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) and SIPC member, and committed to the highest levels of professional ethics and standards.

[1] Source: The Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones VentureSource. Includes companies that are privately held, have raised money in the past four years and have at least one venture-capital firm as an investor. Excludes companies that were majority-controlled by an institutional investment firm at one point. Only valuations confirmed by VentureSource or The Journal are included, based on direct investments, not secondary deals. Colors denote region.